Image: The IMO number is visible on bulk carrier, Quest. The vessel’s homeport is Monrovia and it is registered with Liberia (Credit: Shutterstock)

A merchant ship is delivered with a range of numbers to help identify it. These numbers change throughout its working life, with only one exception – the IMO (International Maritime Organization) number. A mandatory requirement for all passenger and cargo ships, this alphanumeric number is assigned when a vessel is constructed. It was introduced in 1996 to help reduce fraud and increase safety.

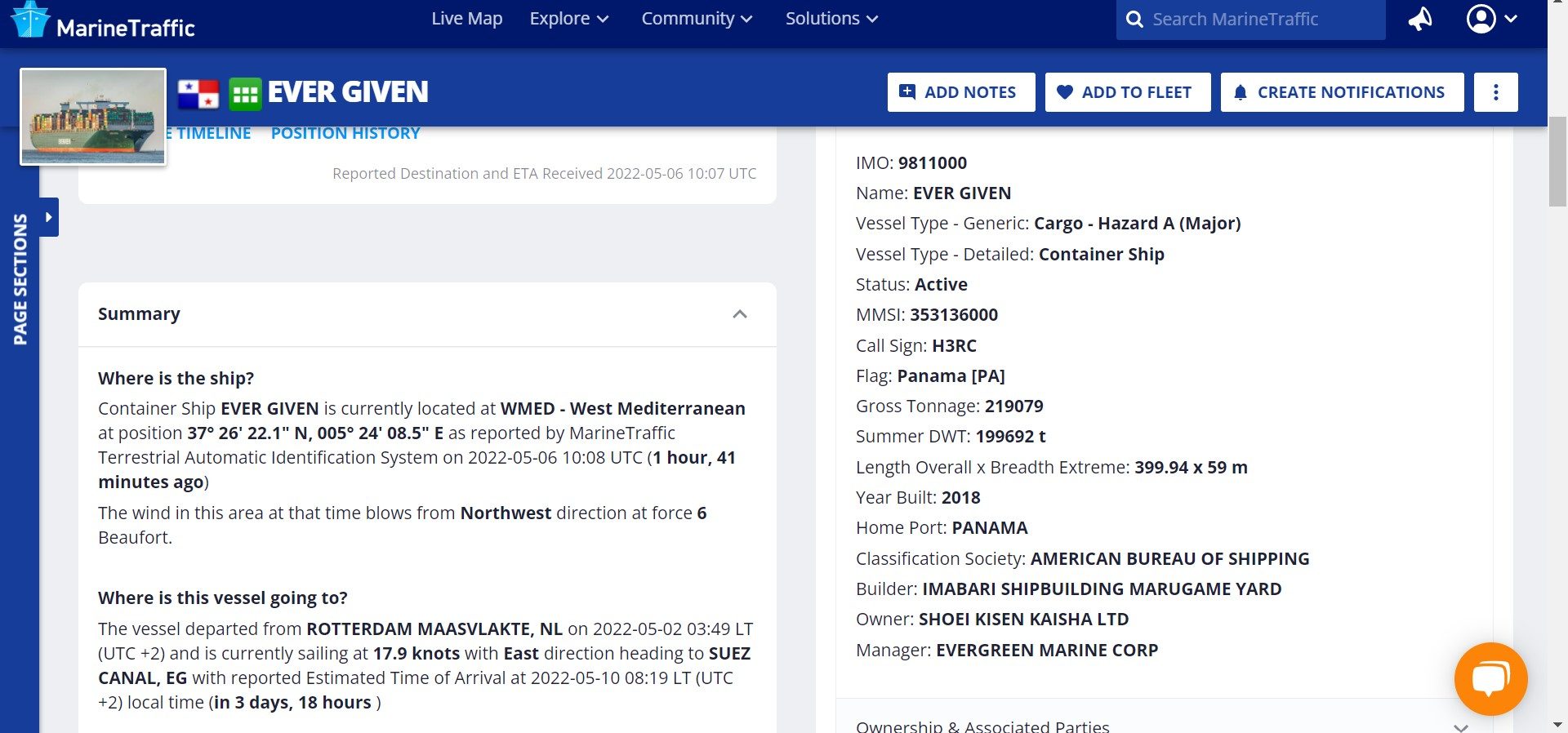

Other numbers assigned to a ship can be changed. To give a couple of examples, the company number changes when a ship is sold to a new owner, and the MMSI (Maritime Mobile Service Identity) number can be changed if a vessel changes owner, and must be changed if it’s re-flagged.

The MMSI is used in AIS (Automatic Identification System) transponders and picked up by the ship tracking services, such as MarineTraffic, that identify ships and plot their positions. MarineTraffic also shares the IMO number when presenting ships on its Live Map.

These numbers play an important role in ship identification, which in turn bring transparency and accountability to the industry.

Consider, however, that a ship’s name, colour and owner can change. It can even, with enough redesign, be lengthened or converted into another ship type. When a ship is finally sent to the breaking yard, it can look quite different to the vessel that left the building yard decades earlier.

Related: Vessel details that can be changed in AIS transponders

The same is also true of a vessel’s flag state, which can change multiple times over the years. To assume that a vessel will be registered in the same country as the owner’s business would be incorrect. Today, it is possible for a shipower to register their vessels with any country that offers a ship registration service. Indeed, landlocked Bolivia, with little or no shipping industry, has developed its own ship registry.

Known as ‘open registries’, these flag states typically offer tax incentives and crucially, do not mandate the nationalities of seafarers working aboard. International shipping is governed by various conventions set out by the IMO which are then ratified and enforced by the flag state. These include conventions covering safety and the environment. Vessels which come under a flag state with a poor record will typically be targeted by local port state control inspectors and delayed or detained if any serious deficiencies are found.

Ship registries can be big business, and numerous states tout for shipping companies’ business. A quick Google search reveals a plethora of registries all presenting their advantages over their competitors.

The largest ten flag states, are Panama, Liberia, Marshall Islands, Hong Kong, Bahamas, Singapore, Greece, Malta, China and Cyprus. The International Chamber of Shipping publishes a useful annual flag state performance table detailing the various flags and the conventions which they have ratified.

High quality registries such as the Marshall Islands and Liberia are selective of which vessels they will accept and will look carefully at the safety and operational profile of the owner and vessel. However, flag swapping is overall a relatively simple procedure, and there is nothing to stop an owner changing a vessel’s flag midway through a voyage if desired. Indeed, it is entirely possible for a shipowner to have each of its vessels registered with a different flag state.

MarineTraffic data from the beginning of 2020 to date reveals that the average number of ships changing flag states is around 200 per month. This will typically be due to the sale of the vessel to a new owner.

It also shows that the spread of registries that owners are choosing to flag with is vast. As an example, in January 2021, owners registered their ships across 35 different states. The most popular that month was the Marshall Islands – the third largest registry – which flagged 31 vessels, whilst Panama, the world’s largest, flagged 26 vessels.

On the flip side, 17 owners chose to flag their vessels with states which flagged one vessel each that same month. These states include Tuvalu, Iran and Comoros.

August 2021 was a busy month for the state of Liberia, which picked up 57 more vessels, adding to its already more than 5000-strong fleet.

Movements across vessel-type can also be ascertained from Marine Traffic data. Looking at data from the beginning of this year, 799 ships have moved flag across seven different vessel types – roro, tankers, containers, dry breakbulk, dry bulk, LNG and LPG vessels.

| Vessel Type | Number of vessels – 2022 to end April |

| Ro-ro ships | 49 |

| Tankers | 256 |

| Containerships | 122 |

| Dry breakbulk carriers | 98 |

| Dry bulk carriers | 238 |

| LNG carriers | 9 |

| LPG carriers | 27 |

Importantly, however, flag states not only impose their maritime law, but they must also govern and if necessary enforce their laws, and it’s the flag states responsibility to carry out inspections on vessels that fly their flag. Some flag states are more rigorous in their approach to these duties however, and irresponsible shipowners may see the charm of this arrangement. On the flip side, it has been documented that vessels flying certain flags are more likely to be inspected by port state control.

Further, recent political tensions in Asia and the war in Europe have shown how the choice of flag can also be used to circumvent sanctions and keep ships moving cargo. The protection offered by the flag state’s navy or its allies may also be a consideration.

The advent of modern technology has made the physical flag, also known as an ensign in shipping, almost redundant. Vessels are now required to fly their country’s flag only if they are entering or leaving port.

Whilst the physical flag is less visible, the role of the flag state remains of vital importance for vessel safety and crew welfare, and helps the industry remain accountable for its activities. As a truly international industry it is more difficult to govern, but flag states ensure that no person, or ship, is outside of the law.