The best way for a ship to avoid hitting a whale is to keep their distance. Photo: Shutterstock

Positioned at the fore of a vessel, the ship’s bow is designed to cut through water at a desired speed. A great subject of debate for naval architects, it determines how the ship interacts with water and is the narrowest point of the vessel.

For shipping lines with just-in-time deliveries to make, bow design can enable a speedy service. Bows can also be configured to support other operational agendas, such as to help vessels transit ice floes, and sail in difficult weather conditions.

They can also, unwittingly, be lethal weapons for unfortunate whales and other cetaceans that happen to be in their path.

Ships’ propellers can also deliver fatal injuries to an animal that comes too close.

Whales have very few natural predators. Polar bears, sharks and orcas (killer whales) may target sick young or ageing whales, but their main predator throughout recent history is humans.

Hunted for their meat and blubber for centuries until 1980 when an international agreement banned commercial whaling, certain species of whale declined in number to critical levels. These numbers have recovered only to an extent. Of the 90 species, the 13 largest are considered ‘great whales’ and according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), six of these great whale species are on the endangered list.

“An estimated minimum of 300,000 whales and dolphins are killed each year as a result of fisheries bycatch, while others succumb to a myriad of threats including shipping and habitat loss,” says the WWF.

Despite being some of the largest mammals on earth – the blue whale at 30 metres long is the largest animal ever known to exist on earth – whales will always come off worse than the ship during a collision.

Often the crew of the vessel will not know that a strike has taken place until the vessel is in port, and sobering images of whales lying limp on the ship’s bulbous bow are easy to find online.

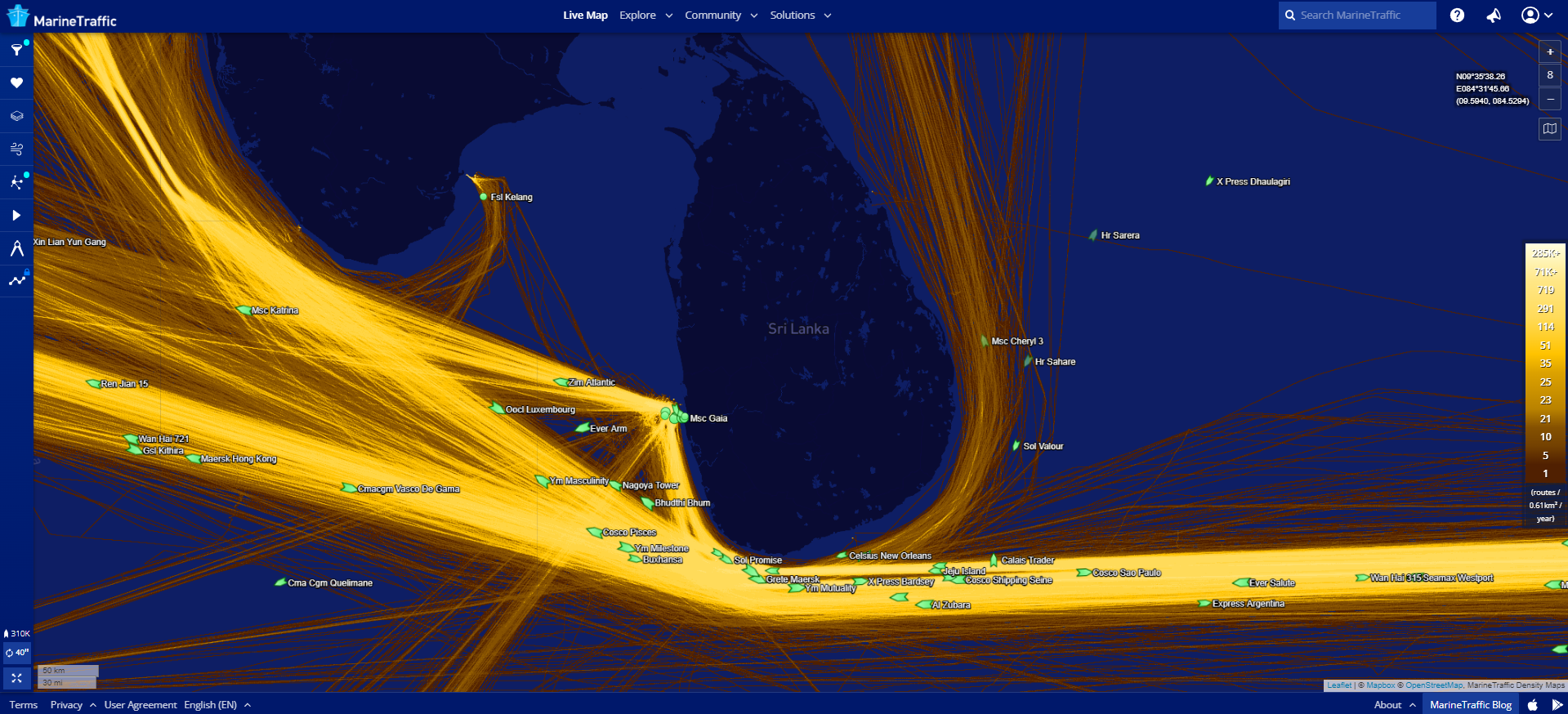

Unfortunately, ships’ sailing routes often overlap with waters used by whales. “Many species of whales feed, play, migrate, rest, nurse, mate, give birth, and socialise in urbanised marine highways, putting them at risk of being struck by passing vessels,” says the Whale and Dolphin Conservation.

In addition, according to the International Fund for Animal Welfare, “certain whale populations are more vulnerable to ship strikes, particularly those found close to developed coastal areas or those found in high numbers in areas with large volumes of shipping traffic”.

Vulnerable whale species include the blue whale that can be found off the coast of Sri Lanka.

These gentle giants also frequent the coast of California where they go to feed. The North Atlantic right whale, meanwhile, can be found on the east coast of the US and Canada, and the Mediterranean Sea is a popular home for the sperm whale.

The number of ships strikes per year is growing.

When looking at United States figures, the Oceanographic magazine writes: “Scientists estimate that more than 80 endangered whales are killed by ships each year just off the west coast of the United States. And the problem is only getting worse as shipping traffic continues to increase.

In 2018 and 2019 we saw the worst years on record for ship collisions off the coast of California, and even so, these records likely only confirm a small fraction of ship strike victims, as most whale carcasses immediately sink or are carried offshore.”

Of course, the easiest way to stop ship strikes is to separate the ships from the whales, but commercial pressures often render this option unfeasible. Other options are significantly reducing speed in high population areas, especially during periods when calves are young and inexperienced, additional lookout on the bridge, rerouting during certain seasons in certain locations and the development of whale sensing equipment.

MarineTraffic is working to prevent ship strikes on whales through a partnership with ‘SAvE Whales’ – or ‘System for the Avoidance of ship-strikes with Endangered whales’.

The multinational inter-disciplinary ‘SAvE Whales’ project was launched in early 2019 to protect endangered whales in the Mediterranean. It brings together expertise from the fields of marine biology, underwater acoustics, applied mathematics, computer networking and informatics. Real-time data supplied by MarineTraffic is also essential to its work.

Company’s founder Dimitris Lekkas said in a 2019 blog: “MarineTraffic always engages closely with the global community to understand the challenges and communicate solutions. In SAvE Whales, we will provide the data management tools necessary for the protection of these important but endangered mammals”.

Other work is also underway, including through the International Maritime Organization, which has adopted ship routeing measures to protect whales from ship strikes during breeding seasons and has also created guidance to shipping lines on minimising the strike risks.

Regional measures have also been taken and organisations established.

One such project is Protecting Blue Whales and Blue Skies. It is a voluntary California coast vessel speed reduction (VSR) programme that offers incentives if shipping companies adopt slower speeds and safer more sustainable practices.

MarineTraffic data suggests that this project and other campaigns are having a positive effect on this coastline. Reporting speed reduction figures in August, the data showed that 65 per cent of vessels that transited San Francisco Bay, also on the US west coast and the Southern California region reduced their speed to 10 nautical miles per hour, or less.

Ships reducing speeds in areas where whales are known to frequent

Our AIS data shows that from May 15 to November 15, 2021, 63% of the vessels (GRT>4999) that transited in the San Fransisco Bay Area & the Southern California region reduced their speed to 10 kn or less [cont]… pic.twitter.com/GIcLynQkLB

— MarineTraffic (@MarineTraffic) August 3, 2022

Elsewhere in the US, in July, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) proposed further measures to help protect the North Atlantic right whale from lethal vessel collisions. The proposed changes would broaden the spatial boundaries and timing of seasonal speed restriction (of 10 knots) areas along the U.S. East Coast. This speed restriction would also be extended to smaller vessels.

Vessel operators are also rising to the challenge.

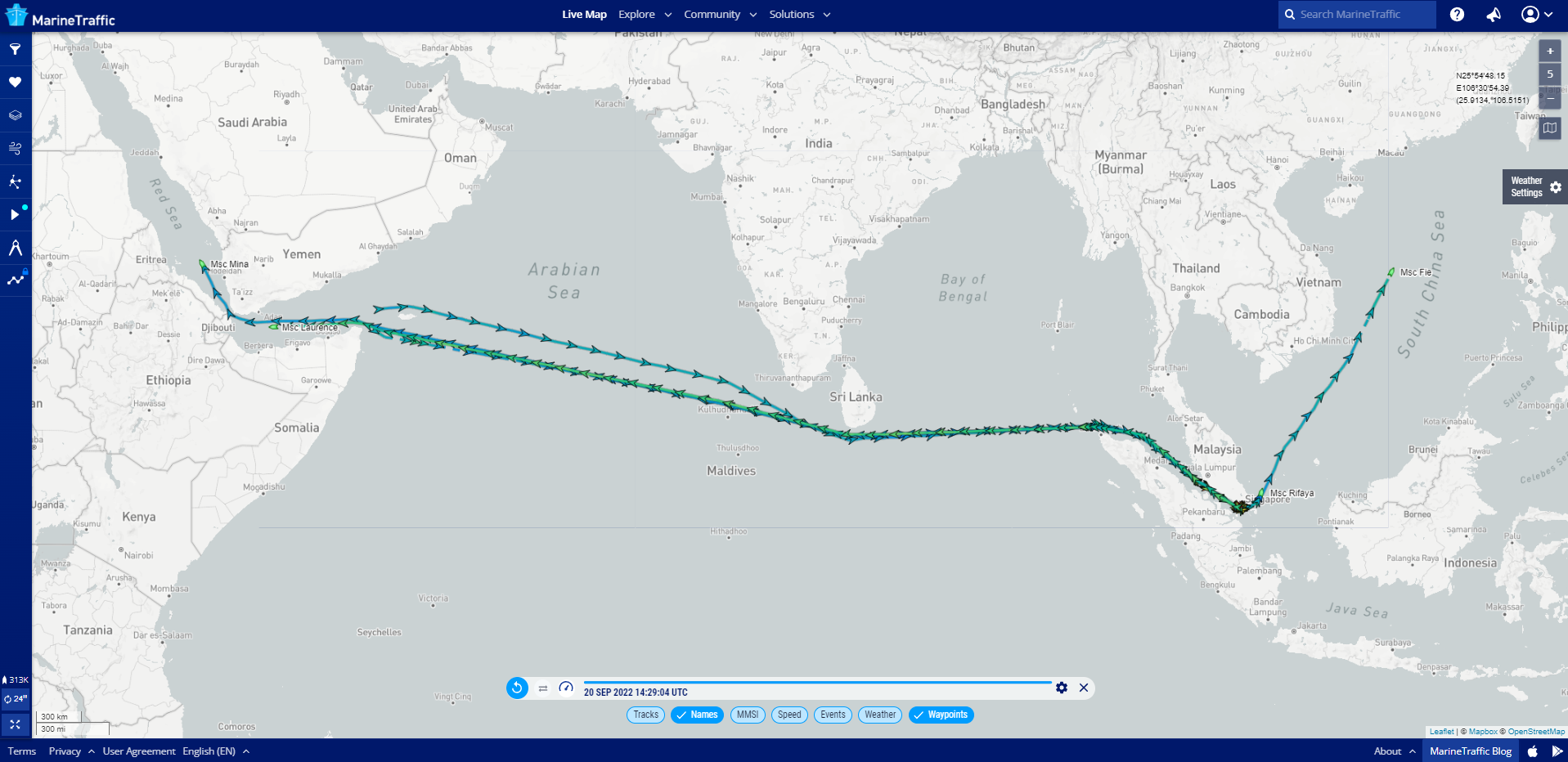

One notable example, is box carrier MSC who earlier this month (September) announced it is re-routing its vessels away from the endangered blue whale population off the coast of Sri Lanka.

The world’s largest container carrier said in a statement that it “began in mid-2022 to voluntarily re-route its vessels passing by Sri Lanka, on a new course that is approximately 15 nautical miles to the south of the current traffic separation scheme (TSS) for commercial shipping.”

These new routes have been decided in line “with the advice of scientists and other key actors in the maritime sector”.

Related: Smarter tracking with improved search and new map layers

Westbound ship traffic is now limited to a latitude between 05 30N and 05 35N, and eastbound traffic is limited to a latitude between 05 24N and 05 29N in order to avoid designated whale and other cetacean habitats.

An exception has been made for vessels embarking and disembarking for safety reasons in Galle (on Sri Lanka’s southwestern tip), including in case of adverse weather. “Additionally, smaller feeder ships sailing around the Bay of Bengal will reduce their speed to less than 10 knots in this area,” says MSC in the statement.

MarineTraffic data shows that MSC vessels are already navigating further away from Sri Lanka’s southern coastline. Investigation into using the MarineTraffic Live Map shows that MSC Fie (sailing from Saudi Arabia to China), MSC Rifaya (Singapore to Morocco), MSC Mina (Singapore to the Suez Canal) and MSC Laurence (Malaysia to Saudi Arabia) were all seen around 15 September, sailing slightly further south than most other container vessels in the region.

It’s not the first time that the Geneva-based carrier has moved to protect whales. In January this year, it re-routed their ships on the west coast of Greece to reduce the risk of collision with endangered sperm whales in the Mediterranean.

“After discussions with four major environmental NGOs, the company decided to take swift action and re-route all of their container vessels in this area to safeguard the critical habitat for the subpopulation of whales. Critical action like this is urgently needed in order to protect the remaining 200 to 300 individuals that remain,” it said in a statement.

Despite the efforts of many, incidents continue to occur. One recent incident reported by Forbes involved a 15-metre humpback whale that washed up in a California bay on the US Pacific coast in August, with a fractured vertebrae and dislocated skull, “suggesting she died after being struck by a ship,” said the article.

Few individuals would want to intentionally hit and hurt or kill a whale. However, shipping’s responsibility to stopping ship strikes extends not only to its obligations to respect these gentle giants as fellow users of the world’s oceans, but also to the environment as a whole.

According to a BBC article published last year, whale faeces has a huge impact on reducing CO2 in our environment. It said:

“Whales feed in the deep ocean, then return to the surface to breathe and poo. Their iron-rich faeces creates the perfect growing conditions for phytoplankton. These creatures may be microscopic, but, taken together, phytoplankton have an enormous influence on the planet’s atmosphere, capturing an estimated 40% of all CO2 produced – four times the amount captured by the Amazon rainforest.”

The industry is already wrangling with hefty measures to reduce its carbon footprint. It seems that one simple measure is to follow MSC’s example and keep well away from our carbon mitigating friends.